Mrs. Hopkins gathered her strength and resolve to climb to the third floor of the Grove Street house. She moved into the servant’s quarters and turned into the small sparse room that Nell had called home for almost a year. She slowly pulled open the drawers to the simple pine bureau. She felt like she was prying somehow, but someone had to gather what little personal effects Nell had and either give them to charity or find someone who knew her and her family in Ireland and post the belongings overseas. She gently pulled the petticoats and chemises, step-ins and stockings and laid them across the bed. The top drawer was usually filled with papers and a small Bible, a diary or other beloved objects such as letters or a pressed dried flower, ribbons, a lock of hair, an old timepiece or, perhaps the only piece of cheap jewelry a servant could afford to own. Mrs. Hopkins gently pulled the drawer open and found a small leather bound Bible, an address book of family in Ireland, a small leather wallet with wages saved and a piece of paper showing the accounting.

Nell’s family was from County Clare on the rugged west coast of Ireland. Nell was twenty at her last birthday and should have been married by that age. Domestics had a hard time of it especially in England but Nell came directly from Ireland to New York City. American servants were required to adhere to strict rules but the rules and customs in Britain were most certainly more draconian. Mrs. Hopkins’ entire life had been spent preserving the structure of this hierarchy. She had attained a certain level of authority and knowledge and enjoyed relaying and advising on all matters pertaining to the running of a household and the managing of domestics among her American counterparts. And although she did not mind suitors for the hired help it was strongly discouraged. Nell was an attractive girl with auburn hair and gray eyes, freckled skin and voluptuous form. There were, however, no notes of adoration or even of interest from the opposite sex. Nell was a good girl and extremely Catholic and she took her duties seriously. It was her livelihood after all. Tucked neatly inside one of the folds of the old wallet was a yellowed piece of paper folded up quite small. As Mrs. Hopkins unfolded it and read the contents it seemed to take her breath away. The writing on the aged letter had faded to such an extent that it was a challenge to make out some of the words. The Irish spelled English a bit differently since they were forced to learn the language and give up their native tongue. She pulled the old straight-backed chair around and sat with the lantern close by.

Liam Connelly had been a fisherman it read. Liam and his wife Aine had six children. And they were listed by age: Mary 14, Mollie 12, Deidre 10, Brian 8, Michael 7 and Malachy 5. It said that Liam had been Nell’s great uncle, a brother to her maternal grandfather and they lived near the Bay of Ballyvaughan not far from the great Burren. One day, and it listed the date as 1869, Liam put the entire family in the small fishing boat for a daytrip to Inishmore. He had told his brother that he was learning to sail and that he could sail around the southern part of Ireland faster and cheaper than trying to walk across it only to have to pay seven fares to cross the Irish Sea to England. The famine had ravaged the western area for a quarter of a century and there seemed no relief from bitter poverty. Liam was willing to risk everything to work in the Liverpool shipyards. But as Mrs. Hopkins read on the entire family disappeared into the Atlantic. It was speculated that a storm rose up and the small vessel capsized in the raging swells. An old Irish legend recounts that people on the seas are sometimes snatched from their boats and taken down into the depths and turned into merrows, dark creatures similar to mermaids but with a preternatural power. Or that the souls of victims drowned in the breakers reappeared in the seals that swam just offshore. Mrs. Hopkins sat for some time in the silence and the stillness gazing over Nell’s possessions. She was perplexed by the familial mystery of an entire line of this girl’s family. Whoever these poor Irish people were they were welcoming Nell into the kingdom of God.

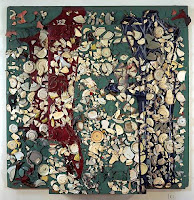

It was late afternoon by the time Chelsea had finished interviewing Julian Schnabel. Julian had been an art star of the eighties making bucket loads of money painting large abstract works with pieces of broken dishes incorporated into them. Rumors circulated by art buyers who purchased Schnabel’s plate-paintings as long-term investments much like traders moving stocks and bonds, were faced with porcelain pieces falling off the paintings rendering them almost worthless. This hearsay was most likely spread by jealous artists wishing they could spin lead into gold as Julian seemed to do. Schnabel put those lies to rest for Chelsea and she appreciated his candor. He was an interesting man filled with rebellious bravado and yet a quiet intelligence that mingled with eccentric thought-processes. She was simultaneously fascinated and repulsed by him. He was gruff and sensitive, hard and refined. Just as she was about to move to her next round of questions Schnabel proceeded to talk about his film career. He had written and directed the critically acclaimed Basquiat and Before Night Falls. His latest achievement residing in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, a wonderfully executed story of a man trapped in his body by a horrific stroke and only able to communicate by blinking one eye. When she saw it she wept copiously and felt withdrawn for days afterward. The films were absolute artistic accomplishments obviously made by a seasoned artist. The colors and composition of each shot and sequence became paintings in and of themselves. She wondered why a painter might turn to the camera as a mistress. Art was so visceral and tangible and sometimes thick and oftentimes not. It was earthy and authentic. It was one-of-a-kind and you could stand in front of it and study the manipulation of paint on canvas. You could learn how the artist expressed him or herself. You could watch how light changed the various layers and textures. It was so subjective. Paintings were endlessly interpretive and wonderfully historic. It was the preferred format of cultural preservation for a millenia. Film seemed removed to her, several steps away from the public. Not that cinema was not an art form, but it required lots of people and technology and chemicals and a darkened room with speakers and a crowd of people to watch. It required an investment of time. Art was timeless. One could stand in front of a painting for a minute or two days or years depending on the beholder’s eye and heart. It was achingly intimate. Film was social. You had to invest at least and hour and a half of time and emotion to get through a film and by the end you may not be satisfied. A painting is immediately satisfying or not. And that was Chelsea’s truth. She seemed to fall for artists and they were a selfish breed. And so everytime she found herself enthralled by a painter or a sculptor she would immediately remember the times she had been burned. Not that she had a lot of experience with relationships but the ones she had been involved in required a lot of work and sacrifice on her end. Her first love had been a long haired Jim Morrison type unsure whether to paint or be a rock-star. He was talented but he could not resist the temptation and allure that a Jim Morrison look alike might get. Relegated to the sidelines, she called it quits. Her next beau was the exact opposite. He was a quiet nerdy type with a crew cut and glasses. As vanity crept in she knew she could do better in the looks department but he was so damn smart and a wildly talented abstract painter drifting into the realms of Anselm Kiefer. However, he was an obsessive compulsive that could never be satisfied. That included her. So she walked away. She had a crush on a girl once who was a scenic painter for the college theatre department but there wasn’t enough of a spark for it to bloom into anything. She was brave enough to pursue the girl but found that a lot of talking was involved and personal information up front that seemed to kill the mystery and so it never got physical and she lost interest. She plunked her digital recorder and notepad in her bag and jumped the Shuttle from Times Square to Grand Central. The city morgue was on the east side of town near Bellevue Hospital. She hoped someone there could direct her to the archives. As she wandered through the sliding glass doors and toward the information desk she felt like a reporter. Like a real investigative reporter. The nurse turned and looked at her blankly. “yes?”

“I’m here to research the archives.” Chelsea said matter of factly.

“Archives.” The nurse said a bit confused. At that moment another nurse walking by holding files and a clipboard interjected. “The morgue archives. They’re not open to the public.” She said and she started to walk away.

“Yes, I know, I’m with the New York Times.” Chelsea said surprised at her blatant lie. “I called earlier. I’m the one investigating the pandemic of World War I.” She continued. She held her breath for a moment knowing they would ask for her press pass and several forms of ID. The nurse with the files eyed her for a moment. “Oh wait. Letitia?” she said and it seemed like eons before Chelsea decided to go with the fib.

“Yeah.” She replied.

“I talked to you this morning, right? On the phone. Girl, I though you were black.” She said in her slightly Jamaican lilt. Then she waved Chelsea to follow her.

“Down the hall to the right and then ask for Jedediah. You tell him Minerva said to take you to the basement.” Then she turned on her heel and disappeared. The corridor was cold and long and uninviting. Restless spirits roamed the area Chelsea thought and even though the day was somewhat warm she felt a chill as she moved down the hallway.

She was ushered into an expansive underground warehouse with Home Depot-like steel shelving housing files upon files of records and death certificates and autopsy reports. Bellevue had been established in 1736, the first hospital in the United States before the colonies became a union, a separate country. It blew her mind.

“What year?” Jedediah said. He was an elderly black man in a dark suit with white hair. He reminded her of Morgan Freeman.

“1918 please.” She said. They walked an aisle the length of a football field when Jedediah maneuvered a metal self-standing ladder and pulled a large box from a high shelf. He escorted her to a small area where a lunchroom table with a few stools set tucked away in a corner.

“Hope you find what you’re lookin’ for, Miss.” He said and then he disappeared down one the aisles leaving her completely alone. The place was outfitted with the best surveillance so she knew she was being watched by several eyes. She began filing through the documents running through the ‘R’s’ first. She had a hunch and she aimed to affirm it.

World War I began in 1914 and she was well aware that the end of the war was not so much from resolving differences as it was from disease. The Spanish flu spread through the trenches killing thousands upon thousands of servicemen. It was the Spanish Flu that ultimately ended the Great War and tensions that were left over reared their ugly head and brought about World War II. The Spanish Flu was a pandemic of epic proportions killing 50 million people in nine months. That was three percent of the entire world’s population in 1919. Astounding. After hours of pouring over documents and all the ‘R’s’ she could find she was about to give up. Yet, there, crumpled between two sheets of paper were the typed notes of Richard Rhys’ death. There was no autopsy because Chelsea had been correct. He died of acute pneumonia due to the Spanish Flu. She held the notes in her hand and she realized she was trembling. It pained her for some reason. She did not know why as she was not even alive when he passed. There were fifty-four years in between his last breath and her first. An entire lifetime and almost three generations and yet there was an odd closeness that overcame her. The notes stated that Mr. Rhys had been a healthy robust man of fifty-seven with no prior conditions or ailments. He was still young, she thought. And that made her ever more melancholy. He was still enjoying life and participating fully in that experience when fate whisked him away taking his final gasp. And it dawned on her that he had drowned. Poor Mr. Rhys had succumbed to the ocean that resided inside of him. Could the sea paintings have foretold his end, she thought? Satisfied with her investigative work she decided she needed to find these paintings. Even if she had to fly to London to do it she would find a way. And although he was a mystery she felt like she was getting to know him, like being reacquainted with an old friend.

Richard woke up suddenly to find Nell hovering over him. Her young nubile face flushed with embarrassment as she fumbled with a wet rag. She averted her eyes and Richard realized he was not wearing a night shirt. He pulled the quilt up over himself and as he did he realized he did not have any underwear on either. Oh God, he thought. He hoped he did not do anything foolish or humiliate himself while asleep. Things happened to men while they slept and he hoped Nell had only just walked in to tend to him.

“The Missus is very worried.” She said in her thick brogue. “You’re not supposed to be here.” She kept her face turned away from him and her voice low. He looked around and realized he was in a room he had never been in before.

“Where am I?” he asked.

“Brooklyn.” Nell replied and she quickly laid the wet rag across his forehead. He noticed he was in a parlor and he recognized the paintings that scattered the room but he could not for the life of him remember painting any of them. It was his style. It was definitely his work, the colors, the strokes, the subject matter mostly. His eyes rested on a large sea painting and he remembered creating several works on that particular subject. It was dark and the swells were turbulent and pieces of wood seemed to float on the surface, tell tale signs of a shipwreck. Looking at the painting made him want to cry suddenly. But he did not.

“When did I do this?” he asked. Nell squinted and her grey eyes seemed blank.

“I don’t remember, sir.” She said obediently averting her eyes.

“Where’s Mrs. Hopkins?” He asked growing a bit more tense.

“Ye shouldn’t move or get excited, sure. Mrs. Hopkins is at the house on Grove Street. I’ve been told to keep ye quiet.” She said nervously. Suddenly there was a loud knock on the door.

“Ashley!” a voice called out. “Ashley!”

“Who the devil is Ashley?” Richard asked and he tried to get up.

“You’re not supposed to be here, I say.” Nell said and she stood up with her finger to her mouth just as a half naked young woman went to answer the door. Richard pulled the quilt up around him as if it could hide him from view. His eyes grew round like saucers completely disoriented.

“Who is that?” he mouthed silently. But Nell only whispered “Shhhhh.” And then she faded away like a fine London mist.